As was the case with adolescence, there were major social and cultural reconfigurations brought about with the medicalization and psychologizing of aging. While Americanists have devoted much attention to what one scholar has called the fin-de-siècle culture of adolescence, representations of old age remain relatively unexamined and undertheorized. Senescence has all the ambitions of his earlier volume and for Hall, this study was understood to be the proper bookend to his scholarly career. Eighteen years later, in 1922, at the end of his academic and administrative career and two years before his own death, Hall published Senescence: The Last Half of Life, an important study of old age. Adolescence had a wide-reaching impact on American culture and transformed the structure and shape of lives and the life narrative. Stanley Hall brought the term adolescence into circulation as a unique phase of life and a subject of psychological and sociological research.

With the 1904 publication of his two-volume Adolescence, American psychologist and president of Clark University G. Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.

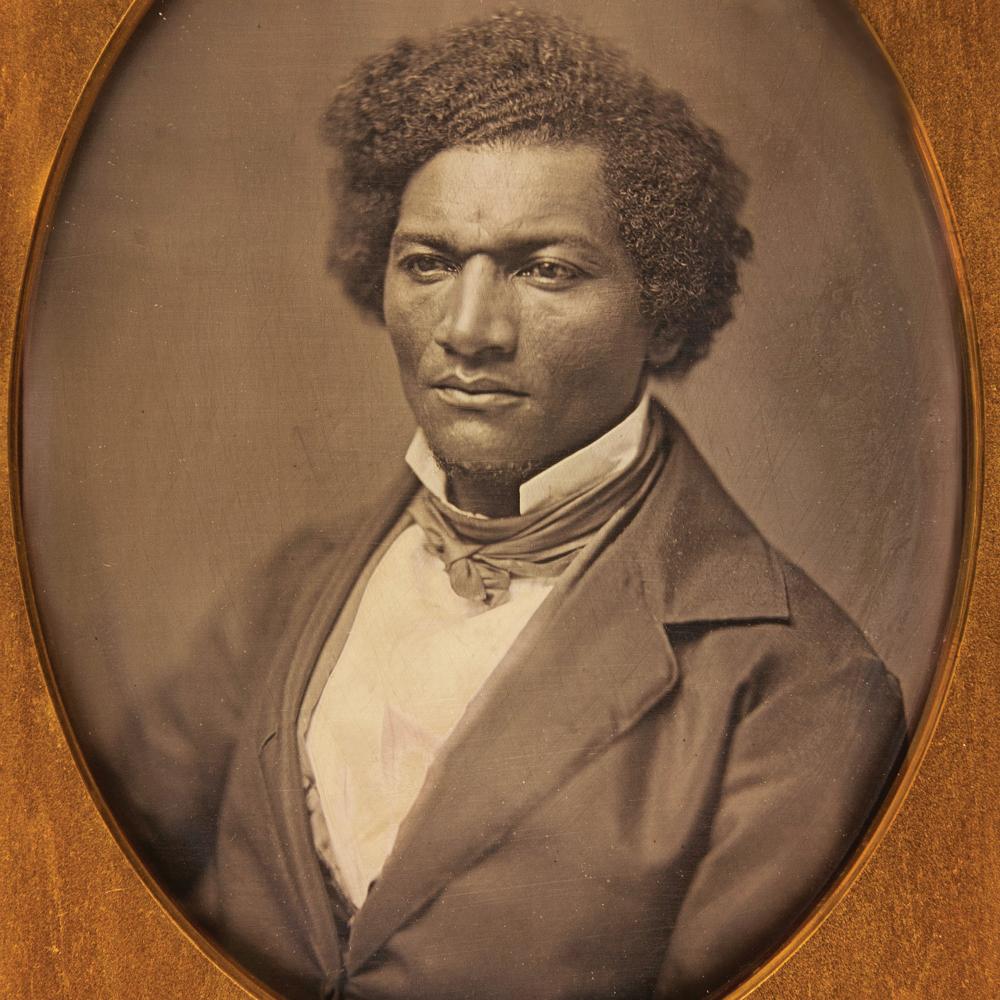

Frederick Douglass,” black and white lithograph by Kurz & Allison (Chicago, no date). Unlike the diachronic narrative fixity of chronological aging, which can only point to decline, old-age autobiography synchronically expands the possibilities of the past by reexamining and making new meaning from past events and experiences.ġ. What I term the old-age autobiographical project is not to be understood as the mere incremental addition of narrative to an already established life story, but rather a process of revising, filling out, and reshaping of the entire life narrative. In the late autobiographical writings of Frederick Douglass, we find a different accounting of the past and a different narrative strategy that adds new dimensions and chapters to our understanding of the senescent subject. The concept of chronological aging suggests an inevitable, even, and incremental process, but this is not the only way in which aging has been experienced. These meanings had special import to those who lived and aged through this period of contested and changing descriptions. Not only were people unsure about what number of lived years qualified one as an old person, but the meaning of old age itself was in flux. In the later years of the nineteenth century, prior to the development of senescence as a unique and distinct stage of life, the meaning of old age was up for debate. While certain long-held prejudices and accounts of aging have remained fairly static, much has changed with regard to how we understand aging and the elderly. Old age and even one’s experience of old age, like so much else, is socially constructed.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)